The Namibians for whom Czechoslovakia is forever home

By Rebecca Davis• 11 March 2021

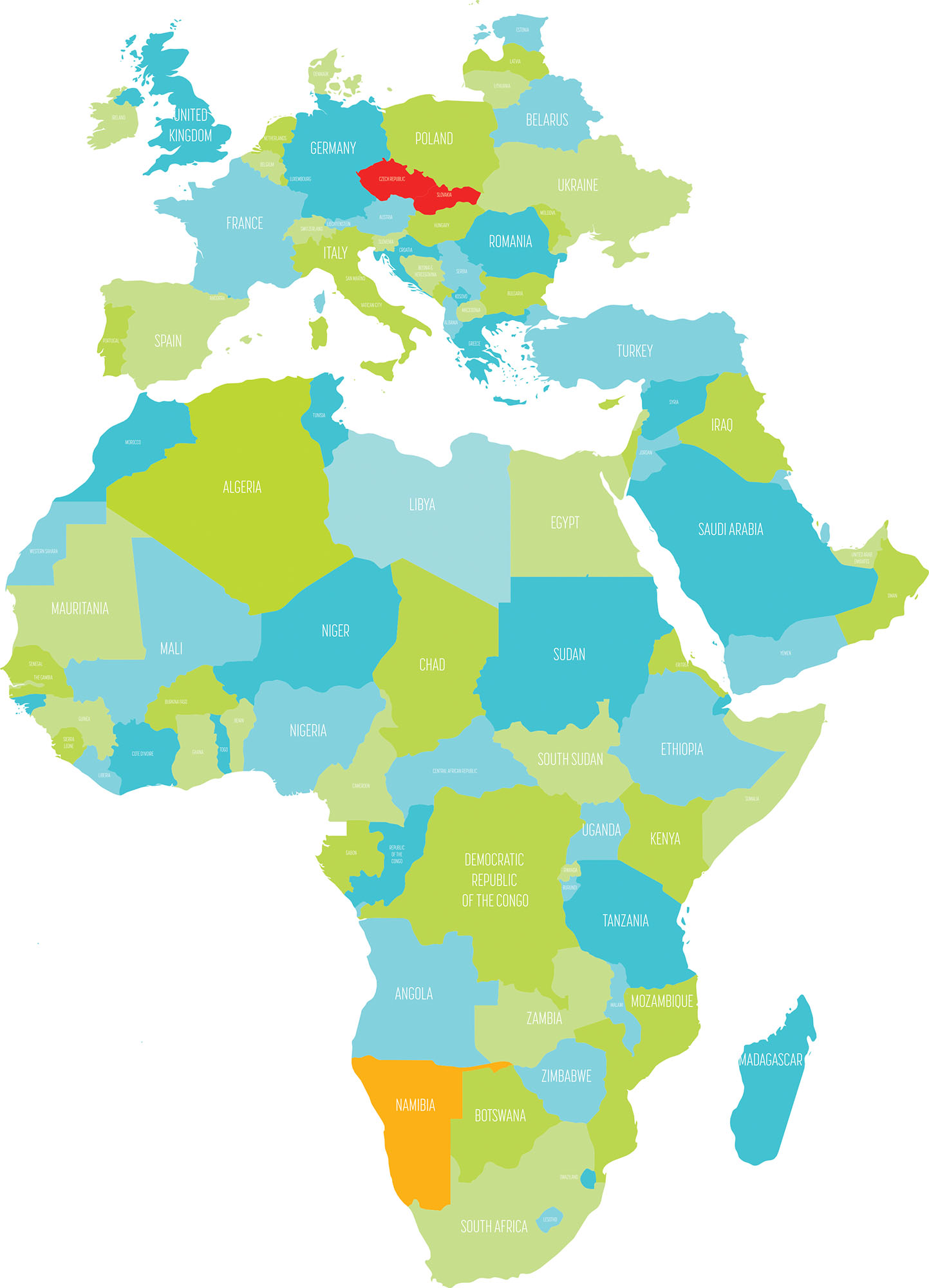

In 1985, during Namibia’s struggle for independence, 56 Namibian children were taken from camps in Zambia and Angola to live in Czechoslovakia. Theirs is a strange and heartbreaking tale of alienation and loss – never before told. Until now. By Rebecca Davis

The official version had it that they were war orphans. In reality, most of the children had at least one parent who was very much alive, and some had two. They were born in the exile camps run by Swapo in Zambia and Angola during the Namibian liberation struggle.

“We cannot get a lot of information, but we know these were not randomly chosen children,” Czech academic Katerina Mildnerova told DM168. “Many of them were the children of prominent liberation fighters.” One was the grandchild of the independent Namibia’s first president, Sam Nujoma.

Little is known, too, about how the children were collected for their long, strange voyage. They were not told where they were going. Czech caregivers would later recall small boys telling them that they had been caught in a net by soldiers before being carried on to a military plane.

Here are the facts, though they read more like fiction: one day in 1985, 56 Namibian children aged between five and nine years old were picked up from Swapo camps, separated from their families and friends, and flown to what was then the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. They were taken to a small village, where they would live, together with their caregivers, in an abandoned castle.

This astonishing historical episode has been made public for the first time in Mildnerova’s book Namibian Czechs, launched in January 2021. A prominent historian of Namibia, contacted by DM168, said she had no knowledge of these events.

Yet it was not an isolated incident. Beginning in the late 1970s, Swapo sent Namibian children to Cuba and to the former East Germany; those stories are better known. The children sent to East Germany are still known in Namibia as the “GDR [German Democratic Republic] kids”, identifiable by their fluent spoken German. One member of this cohort, Lucia Engombe, went on to write a memoir of her experience, Child No 95.

It was by chance that Mildnerova stumbled on the subject. She met two of the so-called Namibian Czechs during her studies and heard their stories firsthand.

“They seemed incredible to me,” she says. “These children were the same age as me, and they were living not far from the place I was living. They were here and we never knew about them!”

At the time of the children’s arrival in Czechoslovakia, Czech media were banned from reporting on them. Swapo was bent on keeping the children’s location a secret to protect them from political enemies, which is why they were kept so isolated from Czech society at first.

Today, there is no reading of this chapter in Namibian history that does not come across as deeply cruel to the children involved. Swapo, now the governing party of Namibia, has maintained official silence on the matter. DM168 reached out to party spokesperson Hilma Nicanor and received no response.

There is little doubt, however, that Swapo believed at the time that it was acting in the best interests of both the children and the future of Namibia. Sending young children to countries run by allied communist governments was, in Mildnerova’s description, “an educational project which had an element of social engineering”.

Says Mildnerova: “Its main purpose was to raise children into obedient soldiers, ardent communists and convinced Namibian patriots.” Namibian tutors were sent with them to ensure that the children were familiarised with Swapo ideology and infused with enthusiasm for the idea of a free Namibia – a country in which, even in its colonial incarnation as South West Africa, none of the children had ever set foot.

Mildnerova’s book is the culmination of several years of fieldwork in the Czech Republic and in Namibia, incorporating archival research and interviews with the Namibian Czechs themselves, former caregivers, teachers and government representatives.

Arrival

“When we came to Czechoslovakia we saw whites everywhere. We thought Swapo had sold us to the enemies to kill us,” one of the Namibian Czechs recalled to Mildnerova.

In the exile camps where they had been living, the children had been warned to be distrustful of white people – just one reason why their sudden uprooting from the camps to the overwhelmingly white Czechoslovakia was so confusing to them. Some of the children arrived traumatised by the liberation war; mood disorders, bed-wetting and sleep terrors were common.

But there are other, sweeter memories. Czech caregivers recalled heavy snow on the day of the children’s arrival. Thinking it was sugar, the children started to eat it and stuff it in their pockets. Accustomed to the deprivations of the exile camps, they could not believe the relative luxury of their Czech castle, or the constant availability of food.

None of the children knew a word of Czech, so they were immediately given intensive language lessons, for hours each day, to ready them for education in the tongue. During the day, the children would speak Czech and be taught by Czech tutors; in the evenings and on weekends, they were addressed in Oshivambo by their Namibian caregivers.

It amounted to what Mildnerova terms “cultural schizophrenia”. She says: “The educational project was confusing and not well understood by the children themselves.”

On an interpersonal level, the children developed extremely warm bonds with their Czech wardens, who saw themselves not just as carrying out their communist duty but as sincerely caring for African orphans they perceived as brutal victims of war. After interviewing eight of their former Czech wardens, Mildnerova says she is convinced that they showed “extraordinary personal commitment”, including making the children part of their families during the holidays.

Perhaps counterintuitively, the Namibian Czechs had far more negative memories of their Namibian caregivers.

“They were very strict. They were also soldiers and they had a clear mission,” says Mildnerova. “They tried to stop the de-nationalisation of the children so they didn’t become Czech because they needed them to be patriots when they came home.”

But Mildnerova also has empathy for the Namibian caregivers, whom she says were in a strange and frustrating position. They, too, had left family behind in Angola. They could not speak the Czech language, and when the children spoke it they assumed they were being made fun of.

After a year, the children were fluent in Czech and had mostly adapted well. They became adept at Czech leisure pursuits, such as hiking and skiing. But they were never integrated into Czech society; everywhere they went, people would stare and touch their skin and hands. The children were also expected to constantly give performances of Ovambo circle dances and Czech folksongs, sometimes performing more than 20 times in a single month.

There were separate, political-themed performances for important days in the Swapo calendar. On these occasions, the children would march in uniform, salute and sing Swapo liberation songs.

The late 1980s and early 1990s were a period of considerable global turmoil, and everything would change politically for both Czechoslovakia and South West Africa within six months after November 1989. In Czechoslovakia, the communist regime fell; the country that would become Namibia won its independence shortly after.

Intense negotiations immediately ensued as to the fate of the Namibian Czechs. Mildnerova says the Czech state wanted the children to finish their education where they were, but Swapo exerted “enormous pressure” for the children to be repatriated.

In 1991, the children – some of whom were now teenagers – were sent to Namibia, the country that they had never visited but of which they had trained so hard to become citizens. “You know no one from us wanted to leave Czechoslovakia… It was like going from paradise to hell,” Mildnerova was told.

Culture shock

The children’s culture shock in Namibia was extreme. Reintegration into families they barely remembered was rendered more traumatic by the fact that the children were not fluent enough in Oshivambo to communicate properly. Czech had become their mother tongue; a language which almost nobody in Namibia, except their 50-odd peers, could understand.

And neither did they have the support of their peers to rely on, since the children were separated and sent to families all over the country. Some went to rural villages, where continuing school was out of the question and their lives became taken up with helping hoe fields and carry water. They were generally viewed with suspicion and resentment by Namibian society more widely, accused of seeing themselves as European and being spoilt.

This is not a story with a happy ending. Of the 56 children, who should now be in their late 30s, six are dead. Mildnerova has been unable to track down another six. About half are unemployed, and only eight have high-ranking jobs.

The advent of WhatsApp and social media has made it easier to keep in touch with each other, and speak Czech together.

Mildnerova says they see their childhood in Czechoslovakia now as a kind of fairytale to which they return mentally when things are tough. That country no longer exists – except as a kind of imagined homeland to which they will always hold passports of the soul. DM168

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-03-11-the-namibians-for-whom-czechoslovakia-is-forever-home/

No comments:

Post a Comment